[ad_1]

In March 2023, the fall of Silicon Valley Bank shocked investors not only because it was unforeseen, but also because of the speed with which it unfolded. That failure has had a domino effect, with Signature Bank falling soon after, followed by Credit Suisse in April 2023 and by First Republic last week. The banks that have fallen so far collectively controlled more deposits than all of the banks that failed in 2008, but unlike that period, equity markets in the United States have stayed resilient, and even within banking, the damage has varied widely across different segments, with regional banks seeing significant draw downs in deposits and market capitalization. The overarching questions for us all are whether this crisis will spread to the rest of the economy and market, as it did in 2008, and how banking as a business, at least in the US, will be reshaped by this crisis, and while I am more a dabbler than an expert in banking, I am going to try answering those questions.

The Value of a Bank

Banks have been an integral part of business for centuries, and while we have benefited from their presence, we have also been periodically put at risk, when banks over reach or get into trouble, with their capacity to create costs that the rest of us have to bear. After every banking crisis, new rules are put into place to reduce or minimize these risks to the economic system, but in spite of these rules or sometimes because of them, there are new crisis. To understand the roots of bank troubles, it is important that we understand how the banking business works, with the intent of creating criteria that we can use to separate good banks from average or bad ones.

The Banking Business Model

The banking business, when stripped down to basics, is a simple one. A bank collects deposits from customers, offering the quid quo pro of convenience, safety and sometimes interest income (on those deposits that are interest-beating) and either lends this money out to borrowers (individuals and businesses), charging an interest rate that is high enough to cover defaults and leave a surplus profit for the bank. In addition, banks can also invest some of the cash in securities, usually fixed-income, and with varying maturities and degrees of default risk, again earning income from these holdings. The profitability of a bank rests on the spread between its interest income (from loans and financial investments) and its interest expenses (on deposits and debt), and the leakages from that spread to cover defaulted loans and losses on investment securities:

To ensure that a bank survives, it’s owners have to hold enough equity capital to buffer against unanticipated defaults or losses.

The Bank Regulators

If you are wondering where bank regulators enter the business model, it is worth remembering that banks predate regulators, and for centuries, were self regulated, i.e., were responsible for ensuring that they had enough equity capital to cover unexpected losses. Predictably, bank runs were frequent and the banks that survived and prospered set themselves apart from the others by being better capitalized and better assessors of default risk than their competition. In the US, it was during the civil war that the National Banking Act was passed, laying the groundwork for chartering banks and requiring them to maintain safety reserves. After a banking panic in 1907, where it fell upon J.P. Morgan and other wealthy bankers to step in and save the system, the Federal Reserve Bank was created in 1913. The Great Depression gave rise to the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933 which restricted banks to commercial banking, with the intent of preventing them from investing their deposit money in riskier businesses. The notion of regulatory capital has always been part of bank regulation, with the FDIC defining “capital adequacy” as having enough equity capital to cover one-tenth of assets. In subsequent decades, these capital adequacy ratios were refined to allow for risk variations across banks, with the logic that riskier assets needed more capital backing than safer ones. These regulatory capital needs were formalized and globalized after the G-10 countries created the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and explicitly created the notions of “risk-weighted assets” and “Tier 1 capital”, composed of equity and equity-like instruments, as well as specify minimum capital ratios that banks had to meet to continue to operate. Regulators were given punitive powers, ranging from restrictions of executive pay and acquisitions at banks that fell below the highest capitalization ranks to putting banks that were undercapitalized into receivership.

The Basel accord and the new rules on regulatory capital have largely shaped banking for the last few decades, and while they have provided a safety net for depositors, they have also given rise to a dangerous game, where some banks arrived at the distorted conclusion that their end game was exploiting loopholes in regulatory capital rules, rather than build solid banking businesses. In short, these banks found ways of investing in risky assets that the regulators did not recognize as risky, either because they were new or came in complex packages, and using non-equity capital (debt and deposits), while getting that capital classified as equity or equity-like for regulatory purposes. The 2008 crisis exposed the ubiquity and consequences of this regulatory capital game, but at great cost to the economy and tax payers, with the troubled assets relief program (TARP) investing $426 billion in bank stocks and mortgage-backed securities to prop up banks that had over reached, mostly big, money-center banks, rather than small or regional banks. The phrase “too big to fail” has been over used, but it was the rationale behind TARP and is perhaps at the heart of today’s banking crisis.

Good and Bad Banks

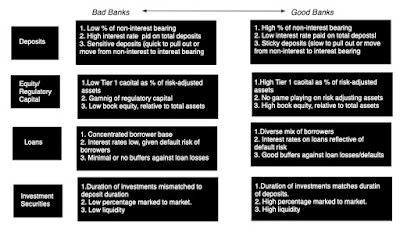

If the banking business is a simple one, what is that separates good from bad banks? If you look back at the picture of the banking business, you can see that I have highlighted key metrics at banks that can help gauge not just current risk but their exposure to future risk.

- Deposits: Every banks is built around a deposit base, and there are deposit base characteristics that clearly determine risk exposure. First, to the extent that some deposits are not interest-bearing (as is the case with most checking accounts), banks that have higher percentages of non-interest bearing deposits start off at an advantage, lowering the average interest rate paid on deposits. Second, since a big deposit base can very quickly become a small deposit base, if depositors flee, having a stickier deposit base gives a bank a benefit. As to the determinants of this stickiness, there are numerous factors that come into play including deposit size (bigger and wealthier depositors tend to be more sensitive to risk whispers and to interest rate differences than smaller ones), depositor homogeneity (more diverse depositor bases tend to be less likely to indulge in group-think) and deposit age (depositors who have been with a bank longer are more sticky). In addition to these bank-specific characteristics, there are two other forces that are shaping deposit stickiness in 2023. One is that the actions taken to protect the largest banks after 2008 have also tilted the scales of stickiness towards them, since the perception, fair or unfair, among depositors, that your deposits are safer at a Chase or Citi than they are at a regional bank. The other is the rise of social media and online news made deposits less sticky, across the board, since rumors (based on truth or otherwise) can spread much, much faster now than a few decades ago.

- Equity and Regulatory Capital: Banks that have more book equity and Tier 1 capital have built bigger buffers against shocks than banks without those buffers. Within banks that have high accumulated high amounts of regulatory capital, I would argue that banks that get all or the bulk of that capital from equity are safer than those that have created equity-like instruments that get counted as equity.

- Loans: While your first instinct on bank loans is to look for banks that have lent to safer borrowers (less default risk), it is not necessarily the right call, when it comes to measuring bank quality. A bank that lends to safe borrowers, but charges them too low a rate, even given their safer status, is undercutting its value, whereas a bank that lends to riskier borrowers, but charges them a rate that incorporates that risk and more, is creating value. In short, to assess the quality of a bank’s loan portfolio, you need to consider the interest rate earned on loans in conjunction with the expected loan losses on that loan portfolio, with a combination of high (low) interest rates on loans and low (high) loan losses characterizing good (bad) banks. In addition, banks that lend to a more diverse set of clients (small and large, across different business) are less exposed to risk than banks that lend to homogeneous clients (similar profiles or operate in the same business), since default troubles often show up in clusters.

- Investment Securities: In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, where banks were burned by their holdings in riskier mortgage-backed securities, regulators pushed for more safety in investment securities held by banks, with safety defined around default and liquidity risk. While that push was merited, and banks with safer and more liquid holdings are safer than banks with riskier, illiquid holdings, there are two other components that also determine risk exposure. The first is the duration of these securities, relative to the duration of the deposit base, with a greater mismatch associated with more risk. A bank that is funded primarily with demand deposits, which invests in 10-year bonds, is exposed to more risk than if invests in commercial paper or treasury bills. The second is whether these securities, as reported on the balance sheet, are marked to market or not, a choice determined (at least currently) by how banks classify these holdings, with assets held to maturity being left at original cost and assets held for trading, being marked to market. As an investor, you have more transparency about the value of what a company holds and, by extension, its equity and Tier 1 capital, when securities are marked to market, as opposed to when they are not.

At the risk of over simplifying the discussion, the picture below draws a contrast between good and bad banks, based upon the discussion above:

Banks with sticky deposits, on which they pay low interest rates (because a high percentage are non-interest bearing) and big buffers on equity and Tier 1 capital, which also earn “fair interest rates”, given default risk, on the loans and investments they make, add more value and are usually safer than banks with depositor bases that are sensitive to risk perceptions and interest rates paid, while earning less than they should on loans and investments, given their default risk.

Macro Stressors

While we can differentiate between good and bad banks, and some of these differences are driven by choices banks make on how they build their deposit bases and the loans and investments that they make with that deposit money, these differences are often either ignored or overlooked in the good times by investors and regulators. If often requires a crisis for both groups to wake up and respond, and these crises are usually macro-driven:

- Recessions: Through banking history, it is the economy that has been the biggest stressor of the banking system, since recessions increase default across the board, but more so at the most default-prone borrowers and investment securities. Since regulatory capital requirements were created in response to one of the most severe recessions in history (the Great Depression), it is not surprising that regulatory capital rules are perhaps most effective in dealing with this stress test.

- Overvalued Asset Classes: While banks should lend money using a borrower’s earnings capacity as collateral, it is a reality that many bankers lend against the value of assets, rather than their earning power. The defense that bankers offer is that these assets can be sold, if borrowers default, and the proceeds used to cover the outstanding dues. That logic breaks down when asset classes get overvalued, since the loans made against the assets can no longer be covered by selling these assets, if prices correct. This boom and bust cycle has long characterized lending in real estate, but became the basis for the 2008 crisis, as housing prices plunged around the country, taking down not just lenders but also holders of real-estate based securities. In short, when these corrections happen, no matter what the asset class involved, banks that are over exposed to that asset class will take bigger losses, and perhaps risk failure.

- Inflation and Interest Rates: Rising inflation and interest rates are a mixed blessing for banks. On the one hand, as rates rise, longer life loans and longer term securities will become less valuable, causing losses.. After all, the market price of even a default-free bond will change, when interest rates change, and bonds that were acquired when interest rates were lower will become less valuable, as interest rates rise. In most years, those changes in rates, at least in developed markets like the US, are small enough that they create little damage, but 2022 was an uncommon year, as the treasury bond rate rose from 1.51% to 3.88%, causing the price of a ten-year treasury bond to drop by more than 19%.

Put simply, every bank holding ten-year treasury bonds in 2022 would have seen a mark down of 19% in the value of these holdings during the year, but as investors, you would have seen the decline in value only at those few banks which classified these holdings as held for sale. That pain becomes worse with bonds with default-risk, with Baa (investment grade) corporate bonds losing 27% of their value. On the other hand, banks that have higher percentages of non-interest bearing deposits will gain value from accessing these interest-free deposits in a high interest world. The net effect will determine how rising rates play out in bank value, and may explain why the damage from the crisis has varied across US banks in 2023.

The Banks in Crisis

It is worth noting that all of the pain that was coming from writing down investment security holdings at banks, from the surge in interest rates, was clearly visible at the start of 2023, but there was no talk of a banking crisis. The implicit belief was that banks would be able to gradually realize or at least recognize these losses on the books, and use the time to fix the resulting drop in their equity and regulatory capital. That presumption that time was an ally was challenged by the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023, where over the course of a week, a large bank effectively was wiped out of existence. To see why Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was particularly exposed, let us go back and look at it through the lens of good/bad banks from the last section:

- An Extraordinary Sensitive Deposit Base: SVB was a bank designed for Silicon Valley (founders, VCs, employees) and it succeeded in that mission, with deposits almost doubling in 2021. That success created a deposit base that was anything but sticky, sensitive to rumors of trouble, with virally connected depositors drawn from a common pool and big depositors who were well positioned to move money quickly to other institutions.

- Equity and Tier 1 capital that was overstated: While SVB’s equity and Tier 1 capital looked robust at the start of 2023, that look was deceptive, since it did not reflect the write-down in investment securities that was looming. While it shared this problem with other banks, SVB’s exposure was greater than most (see below for why) and explains its attempt to raise fresh equity to cover the impending shortfall.

- Loans: A large chunk of SVB’s loan portfolio was composed of venture debt, i.e., lending to pre-revenue and money-losing firms, and backed up by expectations of cash inflows from future rounds of VC capital. Since the expected VC rounds are conditional on these young companies being repriced at higher and higher prices over time, venture debt is extraordinarily sensitive to the pricing of young companies. In 2022, risk capital pulled back from markets and as venture capital investments dried up, and down rounds proliferated, venture debt suffered.

- Investment Securities: All banks put some of their money in investment securities, but SVB was an outlier in terms of how much of its assets (55-60%) were invested in treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. Part of the reason was the surge in deposits in 2021, as venture capitalists pulled back from investing and parked their money in SVB, and with little demand for venture debt, SVB had no choice but to invest in securities. That said, the choice to invest in long term securities was one that was made consciously by SVB, and driven by the interest rate environment in 2021 and early 2022, where short term rates were close to zero and long term rates were low (1.5-2%), but still higher than what SVB was paying its depositors. If there is an original sin in this story, it is in this duration mismatch, and it is this mismatch that caused SVB’s fall.

In short, if you were building a bank that would be susceptible to a blow-up, from rising rates, SVB would fit the bill, but its failure opened the door for investors and depositors to reassess risk at banks at precisely the time when most banks did not want that reassessment done.

In the aftermath of SVB’s failure, Signature Bank was shut down in the weeks after and First Republic has followed, and the question of what these banks shared in common is one that has to be answered, not just for intellectual curiosity, because that answer will tell us whether other banks will follow. It should be noted that neither of these banks were as exposed as SVB to the macro shocks of 2022, but the nature of banking crises is that as banks fall, each subsequent failure will be at a stronger bank than the one that failed before.

- With Signature Bank, the trigger for failure was a run on deposits, since more than 90% of deposits at the bank were uninsured, making those depositors far more sensitive to rumors about risk. The FDIC, in shuttering the bank, also pointed to “poor management” and failure to heed regulatory concerns, which clearly indicate that the bank had been on the FDIC’s watchlist for troubled banks.

- With First Republic bank, a bank that has a large and lucrative wealth management arm, it was a dependence on those wealthy clients that increased their exposure. Wealthy depositors not only are more likely to have deposits that exceed $250,000, technically the cap on deposit insurance, but also have access to information on alternatives and the tools to move money quickly. Thus, in the first quarter of 2023, the bank reported a 41% drop in deposits, triggering forced sale of investment securities, and the realization of losses on those sales.

In short, it is the stickiness of deposits that seems to be the biggest indicator of banks getting into trouble, rather than the composition of their loan portfolios or even the nature of their investment securities, though having a higher percentage invested in long term securities leaves you more exposed, given the interest rate environment. That does make this a much more challenging problem for banking regulators, since deposit stickiness is not part of the regulatory overlay, at least at the moment. One of the outcomes of this crisis may be that regulators monitor information on deposits that let them make this judgment, including:

- Depositor Characteristics: As we noted earlier, depositor age and wealth can be factors that determine stickiness, with younger and wealthier depositors being less sticky that older and poorer depositors. At the risk of opening a Pandora’s box, depositors with more social media presence (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn) will be more prone to move their deposits in response to news and rumors than depositors without that presence.

- Deposit age: As in other businesses, a bank customer who has been a customer for longer is less likely to move his or her deposit, in response to fear, than one who became a customer recently. Perhaps, banks should follow subscriber/user based companies in creating deposit cohort tables, breaking deposits down based upon how long that customer has been with the bank, and the stickiness rate in each group.

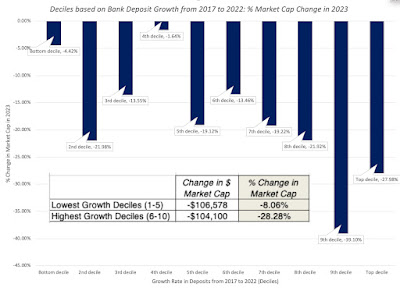

- Deposit growth: In the SVB discussion, I noted that one reason that the bank was entrapped was because deposits almost doubled in 2021. Not only do very few banks have the capacity to double their loans, with due diligence on default risk, in a year, but these deposits, being recent and large, are also the least sticky deposits at the bank. In short, banks with faster growth in their deposit bases also are likely to have less sticky depositors.

- Deposit concentration: To the extent that the deposits of a bank are concentrated in a geographic region, it is more exposed to deposit runs than one that has a more geographically diverse deposit base. That would make regional bank deposits more sensitive that national bank deposits, and sector-focused banks (no matter what the sector) more exposed to deposit runs than banks that lend across businesses.

Some of this information is already collected at the bank level, but it may be time for bank regulators to work on measures of deposit stickiness that will then become part of the panel that they use to judge exposure to risk at banks.

The Market Reaction

The most surprising feature of the 2023 banking crisis has been the reaction of US equity markets, which have been resilient, rising in the face of a wall of worry. To illustrate how the market reaction has played out at different levels, I looked at four indices, starting with the S&P 500, moving on the S&P Financials and Banks Index to the S&P Select Bank Index and finally, the S&P Regional Bank Index.

The S&P 500 index is up 6.5% this year, indicative of the resilience on the part of the market, or denial on the part of investors, depending on your perspective. The S&P Financial Sectors index is down 5.72%, but the S&P Select Banks index is down 26.2% and the regional bank index has taken a pummeling, down more than 35%. The damage from this banking crisis, in short, has been isolated to banks, and within banks, has been greater at regional banks than at the national banks.

The conventional wisdom seems to bethat big banks have gained at the expense of smaller banks, but the data is more ambiguous. I looked at the 641 publicly traded US banks, broken down by market capitalization at the start of 2023 into ten deciles and looked at the change in aggregate market cap within each decile.

As you can see the biggest percentage declines in market cap are bunched more towards the bigger banks, with the biggest drops occurring in the eighth and ninth deciles of banks, not the smallest banks. After all, the highest profile failures so far in 2023 have been SVB, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank, all banks of significant size.

If my hypothesis about deposit stickiness is right, it is banks with the least stick deposits that should have seen the biggest declines in market capitalization. My proxies for deposit stickiness are limited, given the data that I have access to, but I used deposit growth over the last five years (2017-2022) as my measure of stickiness (with higher deposit growth translating into less stickiness):

The results are surprisingly decisive, with the biggest market capitalization losses, in percentage terms, in banks that have seen the most growth in deposits in the last five years. To the extent that this is correlated with bank size (smaller banks should be more likely to see deposit growth), it is by no means conclusive evidence, but it is consistent with the argument that the stickiness of deposits is the key to unlocking this crisis.

Implications

I do believe that there are more dominos waiting to fall in the US banking business, with banks that have grown the most in the last few years at the most risk, but I also believe that unlike 2008, this crisis will be more likely to redistribute wealth across banks than it is to create costs for the rest of us. Unlike 2008, when you could point to risk-seeking behavior on the part of banks as the prime reason for banking failures, this one was triggered by the search for high growth and a failure to adhere to first principles when it comes to duration mismatches. That said, I would expect the following changes in the banking structure:

- Continued consolidation: Over the last few decades, the US banking business has consolidated, with the number of banks operating dropping 14,496 in 1984 to 4,844 in 2022. The 2023 bank failures will accelerate this consolidation, especially as small regional banks, with concentrated deposit bases and loan portfolios are assimilated into larger banks, with more diverse structure.

- Bank profitability: For some, that consolidation is worrisome since it raises the specter of banks facing less competition and thus charging higher prices. I may be naive but I think that as banks consolidate, they will struggle to maintain profitability, and perhaps even see profits drop, as disruptors from fintech and elsewhere eat away at their most profitable segments. In short, the biggest banks may get bigger, but they may not get more profitable.

- Accounting rule changes for banks: The fact that SVB’s failure was triggered by a drop in value of the bank’s investments in bonds and mortgage backed securities, and that this write down came as a shock to in investors, because SVB classified these securities as being held till maturity (and thus not requiring of mark-to-market) will inevitably draw the attention of accounting rule writers. While I don’t foresee a requirement that every investment security be marked to market, a rule change that will create its own dangers, I expect the rules on when securities get marked to market to be tightened.

- Regulatory changes: The 2023 crises have highlighted two aspects of bank behavior that are either ignored or sufficiently weighted into current regulatory rules on banks. The first is duration mismatches at banks, which clearly expose even banks that invest in default free securities, like SVB, to risk. The other is deposit stickiness, where old notions of when depositors panic and how quickly they react will have to be reassessed, given how quickly risk whispers about banks turned into deposit flight at First Republic and Signature Bank. I expect that there will be regulatory changes forthcoming that will try to incorporate both of these issues, but I remain unsure about the form that these changes will take.

I know I have said very little in this post about whether banks are good investments today, either collectively or subsets (large money center, regional etc.), and have focused mostly on what makes for good and bad banks. The reason is simple. Investing is not about judging the quality of businesses, but about buying companies at the right price, and that discussion requires a focus on what expectations markets are incorporating into stock prices. I will address the investing question in my next post, which I hope to turn to very soon!

YouTube Video

[ad_2]