[ad_1]

A few days ago, I valued Instacart ahead of its initial public offering, and noted that the reception that the stock gets will be a good barometer of where risk capital stands in the market, right now. After a buzzy open, when the stock jumped from its offering price of $30 a share to $42, the stock has quickly given up those gains and now trades at below to its offer price. In this post, I will look at another initial public offering, Birkenstock, that is likely to get more attention in the next few weeks, given that it is targeting to go public at a pricing of about €8 billion, for its equity, in a few weeks. Rather than make this post all about valuing Birkenstock, and comparing that value to the proposed pricing, I would like to use the company to discuss how intangible assets get valued in an intrinsic valuation, and why much of the discussion of intangible valuation in accounting circles is a reflection of a mind-set on valuation that often misses its essence.

The Value of Intangible Assets

Accounting has historically done a poor job dealing with intangible assets, and as the economy has transitioned away from a manufacturing-dominated twentieth century to the technology and services focused economy of the twenty first century, that failure has become more apparent. The resulting debate among accountants about how to bring intangibles on to the books has spilled over into valuation practice, and many appraisers and analysts are wrongly, in my view, letting the accounting debate affect how they value companies.

The Rise of Intangibles

While the debate about intangibles, and how best to value them, is relatively recent, it is unquestionable that intangibles have been a part of valuation, and the investment process, through history. An analyst valuing General Motors in the 1920s was probably attaching a premium to the company, because it was headed by Alfred Sloan, viewed then a visionary leader, just as an investor pricing GE in the 1980s was arguing for a higher pricing, because Jack Welch was engineering a rebirth of the company. Even a cursory examination of the the Nifty Fifty, the stocks that drove US equities upwards in the early 1970s, reveals companies like Coca Cola and Gilette, where brand name was a significant contributor to value, as well as pharmaceutical companies like Bristol-Myers and Pfizer, which derived a large portion of their value from patents. In fact, IBM and Hewlett Packard, pioneers of the tech sector, were priced higher during that period, because of their technological strengths and other intangibles. Within the investment community, there has always been a clear recognition of the importance of intangibles in driving investment value. In fact, among old-time value investors, especially in the Warren Buffet camp, the importance of having “good management’ and moats (competitive advantages, many of which are intangible) represented an acceptance of to how critical it is that we incorporate these intangible benefits into investment decisions.

With that said, it is clear that the debate about intangibles has become more intense in the last two decades. One reason is the perception that intangibles now represent a greater percent of value at companies and are a significant factor in more of the companies that we invest in, than in the past. While I have seen claims that intangibles now account for sixty, seventy or even ninety percent of value, I take these contentions with a grain of salt, since the definition of “intangible” is elastic, and some stretch it to breaking point, and the measures of value used are questionable. A more tangible way to see why intangibles have become a hot topic of discussion is to look at the evolution of the top ten companies in the world, in market capitalization, over time:

In 1980, IBM was the largest market cap company in the world, but eight of the top ten companies were oil or manufacturing companies. With each decade, you can see the effect of regional and sector performance in the previous decade; the 1990 list is dominated by Japanese stocks, reflecting the rise of Japanese equities in the 1980s, and the 2000 list by technology and communication companies, benefiting from the dot-com boom. Looking at the top ten companies in 2020 and 2023, you see the dominance of technology companies, many of which sell products that you cannot see, often in production facilities that are just as invisible.

The other development that has pushed the intangible discussion to the forefront is a sea change in the characteristics of companies entering public markets. While companies that were listed for much of the twentieth century waited until they had established business models to go public, the dot-com boom saw the listing of young companies with growth potential but unformed business models (translating into operating losses), and that trend has continued and accelerated in this century. The graph below looks at the revenues and profitability of companies that go public each year, from 1980 to 2020:

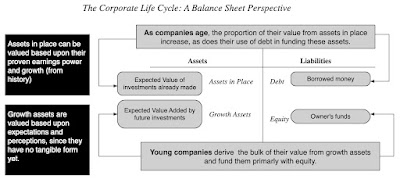

As you can see, the percent of money-making companies going public has dropped from more than 90% in the 1980s to less than 20% in 2020, but at the same time, while also reporting much higher revenues, reporting the push by private companies to scale up quickly. In valuing these companies, investors and analysts face a challenge, insofar as much of the values of these firms came from expectations of what they would do in the future, rather than investments that they have already made. I capture this effect in what I call a financial balance sheet:

While you can value assets-in-place, using historical data and the information in financial statements, in assessing the value of growth assets, you are making your best assessments of investments that these companies will make in the future, and these investments are formless, at least at the moment.

The Accounting Challenge with Intangibles

The intangible debate is most intense in the accounting community, with both practitioners and academics arguing about whether intangibles should be “valued”, and if so, how to bring that value into financial statements. To see why the accounting consequences are likely to be dramatic, consider how these choices will play out in the balance sheet, the accountants’ attempt to encapsulate what a business owns, what it owes and how much its equity is worth.

There are inconsistencies in how accountants measure different classes of assets, and I incorporate them into my picture above, leaving the intangible assets section as the unknown: Any changes in accounting rules on measuring the value of intangibles, and bringing them on the balance sheet, will also play out as changes on the other side of the balance sheet, primarily as changes in the value of assessed or book equity. Put simply, if accountants decide to bring intangible assets like brand name, management quality and patent protection into asset value will increase the value of book equity, at least as accountants measure it, in that company.

In their attempt to bring intangible assets on to balance sheets, accountants face a barrier of their own creation, emanating from how they treat the expenditures incurred in building up these assets. To understand why, consider how fixed assets (such as plant and equipment and equipment) become part of the balance sheet. The expenditures associated with acquiring these fixed assets are treated as capital expenditures, separate from operating expenses, and only the portion of that expenditure (depreciation or amortization) that is assumed to be related to the current year’s operations is treated as an operating expense. The unamortized or un-depreciated portions of these capital expenses are what we see as assets on balance sheets. The expenses that result in intangible asset acquisitions are, for the most part, not treated consistently, with brand name advertising, R&D expenses and investments in recruiting/training, the expenses associated with building up brand name, patent protection and human capital, respectively, being treated as operating, rather than capital, expenses. As a consequence of this mistreatment, I have argued that not only are the biggest assets, mostly intangible, at some companies kept off the balance sheet, but their earnings are misstated:

There are ways in which accounting can fix this inconsistency, but it will result in an overhaul of all of the financial statements, and companies and investors balk at wholesale revamping of accounting numbers (EBITDA, earnings per share, book value) that they have relied on to price these firms.

So, how far has accounting come in bringing intangible assets on to balance sheets? One way to measure progress on this issue is to look at the portion of the book value of equity at US companies that comes from tangible assets, in the chart below:

Looking across all US firms from 1980 to 2022, the portion of book value of equity that comes tangible assets has dropped from more than 70% in 1998 to about 30% in 2022. That would suggest that intangible assets are being valued and incorporated into balance sheets much more now than in the past. Before you come to that conclusion, though, you may want to consider the breakdown of the intangible assets on accounting balance sheets, which I do in the graph below:

There is another measure that you can use to see the futility, at least so far, of accounting attempts to value intangibles. In the graph below, I look at the aggregated market capitalization of companies, in 2022, which should incorporate the pricing of intangibles by the market, and compare that value to book value (tangible and intangible), by sector, reflecting accounting attempts to value these same intangibles.

The sectors where you would expect intangible assets to be the largest portion of value are consumer products (brand name) and technology (R&D and patents). These are also the sectors with the lowest book values, relative to market value, suggesting that whatever accountants are doing to bring in intangibles in these companies into book value is not having a tangible effect on the numbers.

In sum, the accounting obsession with intangibles, and how best to deal with them, has not translated into material changes on balance sheets, at least with GAAP in the United States. It is true that IFRS has moved faster in bringing intangible assets on to balance sheets, albeit not always in the most sensible ways, but even with those rules in place, progress on bringing intangible assets onto balance sheets has been slow. To be frank, I don’t think accounting rule writers will be able to handle intangibles in a sensible way, and the barriers lie not in rules or models, but in the accounting mindset. Accounting is backward-looking and rule-driven, making it ill equipped to value intangibles, where you have no choice, but to be forward looking, and principle-driven.

The Intrinsic Value of Intangibles

I have been teaching and writing about valuation for close to four decades now, and I have often been accused of giving short shrift to intangible assets, because I don’t have a session dedicated to valuing intangibles, in my valuation class, and I don’t have entire books, or even chapters of my books, on the topic. While it may seem like I am in denial, given how much value companies derive from assets you cannot see, I have never felt the need to create new models, or even modify existing models, to bring in intangibles. In this section, I will explain why and make the argument that if you do intrinsic valuation right, intangibles should be, with imagination and very little modification of existing models, already in your intrinsic value.

To understand intrinsic value, it is worth starting with the simple equation that animates the estimation of value, for an asset with n years of cash flows:

Thus, the intrinsic value of an asset is the present value of the expected cash flows on it, over its lifetime. When valuing a business, where cash flows could last for much longer (perhaps even forever), this equation can be adapted:

In this equation, for anything, tangible or not, has to show up in either the expected cash flows or in the risk (and the resulting discount rate); that is my “IT” proposition. This proposition has stood me in good stead, in assessing the effect on value of just about everything, from macro variables like inflation to buzzwords like ESG.

Using this framework for assessing intangible assets, from brand name to quality management, you can see that their effect on value has to come from either higher expected cash flows or lower risk (discount rates). To provide more structure to this discussion, I reframe the value equation in terms of inputs that valuation analysts should be familiar with – revenue growth, operating margins and reinvestment, driving cash flows, and equity and debt risk, determining discount rates and failure risk.

In the picture, I have highlight some of the key intangibles and which inputs are mostly likely to be affected by their presence.

- It is the operating margin where brand name, and the associated pricing power, is likely have its biggest effect, though it can have secondary effects on revenue growth and even the cost of capital.

- Good management, another highly touted intangible, will manifest in a business being able to deliver higher revenue growth, but also show up in margins and reinvestment; the essence of superior management is being able to find growth, when it is scarce, while maintaining profitability and not reinvesting too much.

- Connections to governments and regulators, an intangible that is seldom made explicit, can affect value by reducing failure risk and the cost of debt, while increasing growth and or profitability, as the company gets favorable treatment on bids for contracts.

This is not a comprehensive list, but the framework applies to any intangible that you believe may have an effect on value. This approach to intangibles also allows you to separate valuable intangibles from wannabe intangibles, with the latter, no matter how widely sold, having little or no effect on value. Thus, a company that claims that it has a valuable brand name, while delivering operating margins well below the industry average, really does not, and the effect of ESG on value, no matter what its advocates claim, is non-existent.

It is true that this approach to valuing intangibles works best for a company with a single intangible, whether it be brand name or customer loyalty, where the effect is isolated to one of the value drivers. It becomes more difficult to use for companies, like Apple, with multiple intangibles (brand name, styling, operating system, user platform). While you can still value Apple in the aggregate, breaking out how much of that value comes from each of the intangibles will be difficult, but as an investor, why does it matter?

The Birkenstock IPO: A Footwear company with intangibles

If you have found this discussion of intangibles abstract, I don’t blame you, and I will try to remedy that by applying my intrinsic value framework to value Birkenstock, just ahead of its initial public offering. As a company with multiple intangible components in its story, it is well suited to the exercise, and I will try to not only estimate the value of the company with the intangibles incorporated into the numbers, but also break down the value of each of its intangibles.

The Lead In

Birkenstock is primarily a footwear company, and to get perspective on growth, profitability and reinvestment in the sector, I looked at all publicly traded footwear companies across the globe. the table below summarizes key valuation metrics for the 86 listed footwear companies that were listed as of September 2023.

In the aggregate, the metrics for footwear companies are indicative of an unattractive business, with more than half the listed companies seeing revenues shrink in the decade, leading into 2022 and more than quarter reporting operating losses. However, many of these companies are small companies, with a median revenue at $170 million, struggling to stay afloat in a competitive product market. Since Birkenstock generated revenues of $1.4 billion in the twelve months leading into its initial public offering, with an expectation of more growth in the future, I zeroed in on the twelve largest companies in the apparel and footwear sector, in market capitalization, and looked at their operating metrics:

As you can see, these companies look very different from the sector aggregates, with solid revenue growth (median compounded growth rate of 8.66% a year, for the last decade) and exceptional operating margins (gross margins close to 70% and operating margins of 24%). Each of the companies also has a recognizable or many recognizable brand names, with LVMH and Hermes topping the list. In this business, at least, brand name seems to be dividing line between success and mediocrity, and having a well-recognized brand name contributes to growth and profitability. It is this grouping that I will draw on more, as I look valuing Birkenstock.

Birkenstock’s History

In my work on corporate life cycles, I talk about how companies age, and how importance it is that they act accordingly. Generally, as a company moves across the life cycle, revenue growth eases, margins level off and there is less reinvestment. As a business that has been around for almost 250 years, Birkenstock should be a mature or even old company, but it has found a new lease on life in the last decade.

Birkenstock was founded in 1774 by Johann Adam Birkenstock, a Germany cobbler, and it stayed a family business for much of its life. In the decades following its founding, the company modified and adapted its footwear offerings, catering to wealthy Europeans in the growing German spa culture in the 1800s, and modifying its product line, adding flexible insoles in 1896 and pioneering arch supports in 1902. During the 1920s and 1930s, the company carved out a market around comfort and foot care, partnering with physicians and podiatrists, offering solutions for customers with foot pain. In 1963, the company introduced its first fitness sandal, the Madrid, and sandals now represent the heart of Birkenstock’s product line.

Along the way, serendipity played a role in the company’s expansion. In 1966, a Californian named Margot Fraser, when visiting her native Germany, discovered that Birkenstocks helped her tired and hurting feet, and she convinced Karl Birkenstock to try selling the company’s sandals in California. It is said that Karl advanced her credit, and helped her persuade reluctant California retailers to carry the company’s unconventional footwear in their stores. That proved timely, since people protesting against the war and society’s ills latched on to these sandals, making them them symbolic footwear for the rebellious. in the 1990s, the brand had a rebirth, when a very young Kate Moss wore it for a cover story, and it became a hot brand, especially on college campuses. Today, Birkenstock gets more than 50% of its revenues in the United States, with multiple celebrities among its customers. The company’s prospectus does a good job painting a picture of both the product offerings and customer base, leading into the IPO, and I have captured those statistics in the picture below:

Unlike some in its designer and brand name peers, the company’s products are not exorbitantly over priced and the company’s best seller, the Arizona, sells for close to $100. While the company sells more shoes to women than men, it sells footwear to a surprisingly diverse customer base, in terms of income, with 20% of its sales coming from customers who earn less than $50,000 a year, and in terms of age, with almost 40% of its revenues coming from Gen X and Gen Z members.

For much of its history, Birkenstock was run as a family business, capital constrained and with limited growth ambitions, perhaps explaining its long life. The turning point for the company, to get to its current form, occurred in 2012, when the family, facing internal strife, turned control of the company over to outside managers, choosing Markus Bensberg, a company veteran, and Oliver Reichert, a consultant, as co-CEOs of the company. Reichert, in particular, was a controversial pick since he was not only an outsider, but one with little experience in the shoe business, but the choice proved to be inspired. With an assist again from serendipity, when Phoebe Philo exhibited a black mink-lined Arizona on a Paris catwalk in 2012, leading to collaborations with high-end designers like Dior, the company has found a new life as a growth company, with revenues rising from €200 million in 2012 to more than €1.4 billion in the twelve months leading into the IPO, representing an 18.2% compounded annual growth rate over the decade:

The surge in revenues has been particularly pronounced since 2020, the COVID year, with different theories on why the pandemic increased demand for the product; one is that people working from home chose the comfort of Birkenstocks over uncomfortable work shoes. The company’s growth has come with solid profitability, and the table below shows key profit metrics over the last three years:

|

Note that the company’s operating and gross margins, at least in the last two years, match up well with the operating margins of the large, brand name apparel & footwear companies that we highlighted in the last section. It may be early to value brand name, but the company certainly has been delivering margins that put it in the brand name group.

The strong growth since 2020 provide a strong basis for why the company is planning its public offering now, but there is another factor that may explain the timing. In 2021, the family sold a majority stake in the firm to L. Catterton, an LVMH-backed private equity firm, at an estimated value in excess of €4 billion Euros. That deal was funded substantially with debt, leaving a debt overhang of close to €2 billion, in 2023; the prospectus states that all of of the company’s proceeds from the offering will be used to pay down this debt. That said, the pricing for the offering has increased since news of it was first floated in July, with €6 billion plus pricing in initial reports increasing to €8 billion in early September and to €9.2 billion in the most recent news stories. The company has picked up anchor investors along the way, with the Norwegian sovereign fund planning to buy €300 million of the initial offering.

Birkenstock’s Intangibles

Birkenstock is a good vehicle for identifying and valuing intangibles, since it has so many of them, with some more sustainable and more valuable than others:

- Brand Name: It is undeniable that Birkenstock not only has a brand name, in terms of recognition and visibility, but has the pricing power and operating margins to back up that brand name. However, as is often the case, the building blocks that gave rise to the brand name are complex and varied. The first is the uniqueness of the footwear makes the company stand out, with people people either hating its offerings (ugly, clunky, clog) or loving it. Unlike many footwear companies that attempt to copy the hottest styles, Birkenstock marches to its own drummer. The second is that the company’s focus on comfort and foot health, in designing footwear, as well as the use of quality ingredients, is matched by actions. In fact, one reason that the company makes almost all of its shoes still in Germany, rather than offshoring or outsourcing, is to preserve quality, and sticks with time-tested and quality ingredients, is to preserve this reputation. The third is that unlike some of the companies on the big brand name list, Birkenstock’s are not exorbitantly over priced, and has a diverse (in terms of income and age) customer base. In short, its brand name seems to have held up well over the generations.

- Celebrity Customer Base: As I noted earlier, especially as Birkenstocks entered the US market, they attracted a celebrity clientele, and that has continued through today. Birkenstock attracts celebrities in different age groups, from Gwyneth Paltrow & Heidi Klum to Paris Jackson & Kendall Jenner, and more impressively, it does so without paying them sponsorship fees. If the best advertising is unsolicited, Birkenstock clearly has mastered the game.

- Good Management: I tend be skeptical about claims of management genius, having discovered that even the most highly regarded CEOs come with blind spots, but Birkenstock seems to have struck gold with Oliver Reichert. Not only has he steered the company towards high growth, but he has done so without upsetting the balance that lies behind its brand name. In fact, while Birkenstock has entered into collaborative arrangements with other high profile brand names like Dior and Manolo Blank, Reichert has also turned down lucrative offers to collaborate with designers that he feels undermine Birkenstock’s image.

- The Barbie Buzz: For a company that has benefited from serendipitous events, from Margot Fraser’s introduction of its footwear to Americans in 1966 to Phoebe Philo’s sandals on the Paris catwalk in 2012, the most serendipitous event, at least in terms of its IPO, may have been the release of the Barbie movie, this summer. Margot Robbie’s pink Birkenstock sandals in that movie, which has been the blockbuster hit of the year, hyper charged the demand for the company’s footwear. It is true that buzzes fade, but not before they create a revenue bump and perhaps even increase the customer base for the long term.

For the moment, these intangibles are qualitative and fuzzy, but in the next section, I will try to bring them into my valuation inputs.

Birkenstock Valuation

My Birkenstock valuation is built around an upbeat story of continued high growth and sustained operating margins, with the details below:

- Revenue Growth: The company is coming into the IPO, with the wind at its back, having delivered a compounded annual growth rate of 18.2% in revenues in the decade leading into the offering. That said, its revenues now are €1.4 billion, rather than the €200 million they were in 2012, and growth rates will come down to reflect the larger scale. While the average CAGR in revenues for big brand apparel & footwear firms has been 8.66%, I believe that Oliver Reichert and the management team that runs Birkenstock will continue their successful history of opportunistic growth, and be able to triple revenues over the next decade. This will be accomplished with an assist from the Barbie Buzz in year 1 (pushing the growth rate to 25% over the next year) and a compounded growth rate of 15% a year in the following four years.

- Profitability: Birkenstock has had a history of strong operating margins, driven by its brand name and visibility. In the twelve months leading into the IPO, the company reported a pre-tax operating margin of 22.3%, and its margins over the last decade have hovered around 20%. I believe that the strength of the brand name will sustain and perhaps even slightly increase operating margins for the company, with the margin increasing to 23%, over the next year, and to 25% over the following four years.

- Reinvestment: Birkenstock has been circumspect in investing for growth, over its history, showing reluctance to move away from its reliance on its German workforce, and in making acquisitions. It has also not been a big spender on brand advertising, using its celebrity clientele as a key component of building and growing its brand I believe that the celebrity clientele effect will allow the company to continue on its path of efficient growth, delivering €2.62 for every euro invested, matching the third quartile of big brand apparel firms.

- Risk: The Catterton acquisition of a majority stake in Birkenstock in 2021 was funded with a significant amount of debt, but the proceeds from the offering are expected to be utilized in paying down debt. The company should emerge from the offering with a debt load on par with other brand name apparel & footwear companies, and the concentration of its production in Germany will reduce exposure to supply chain and country risk.

- IPO Proceeds: News stories suggest that Birkenstock is planning to offer about 21.5 million shares to the public, and use the proceeds (estimated to be €1 billion, at the €45 offering price) to pay down debt. In conjunction, Catterton plans to sell about the same number of shares at the offering as well, reducing its stake in the company, and cashing out on what should be a big win for the private equity player.

To see how these inputs play out in value, I have brought them together in the (dense) valuation picture below. With each of the inputs, I have highlighted both the numbers that I am using, as well as highlighting how much intangibles contribute to each input:

The value that I estimate for Birkenstock, with my inputs on growth, profitability and risk, is about €8.38 billion, about 10% less than the rumored offering pricing, but still well within shouting distance of that number. In case you are tempted to use the company’s many intangibles as the explanation for the difference, note that I have already incorporated them into my inputs and value. To make explicit that effect, I have isolated each intangible and its effect on value in the table below:

To value each intangible, I toggle the input that reflects the intangible on and off to determine how much it changes value. The intangible that has the biggest effect on value is brand name, followed by the strength of the management team, with the Barbie Buzz and Celebrity Effects lagging. Another way of visualizing how these intangibles play into value is to build up to estimated value of equity of €8.38 billion in pieces:

These value judgments are based upon my estimates, and they are, of course, open for debate. For instance, you might argue that the effect of good management on revenue growth is more or less than my estimate, or even that the effects spill over into other inputs (cost of capital, margins and reinvestment), but that is a healthy debate to have.

Pricing Factors

It is undeniable that the Birkenstock IPO will be priced, not valued, and the question of how the stock will do is just as much dependent, perhaps more so, on market mood and momentum, as it is on the fundamentals highlighted in the valuation.

- Looking at news about the company, the timing works well, since the company is coming into the market on a wave of good publicity. Almost every news story that I have read about the company paints a positive picture of it, with laudatory mentions of Oliver Reichert and the company’s products, intermixed with pictures of not only Barbie’s pink Birkenstock but a host of other celebrities.

- It is the market mood that is working against the company, at least at the moment that I am writing this post (October 6, 2023). As I wrote in my post on bipolar markets just a few days ago, the market mood has soured, with the optimism that we had dodged the bullet that was so widely prevalent just a few weeks ago replaced with the pessimism that dark days lie ahead for the global economy and markets.

At its offering pricing of €9.2 billion (€45 to €50 per share), the company and its bankers seem to be betting that the good vibes about the company will outweigh the bad vibes in the market, but that is gamble. As someone who has tried and rejected the Arizona sandal, I am unlikely to be a customer for Birkenstock footwear, but this is a company with a truly unique brand name and a management team that understands the delicate balance between utilizing a brand name well and overdoing it. It is, in my view, a reach at €45 or €50 per share, but if the market turns sour, and the stock drops to below €40, I would be a buyer.

YouTube Video

Attachments

[ad_2]